The Greatest Night In Pop Invites You Into One Of The Biggest Nights In 80’s Music

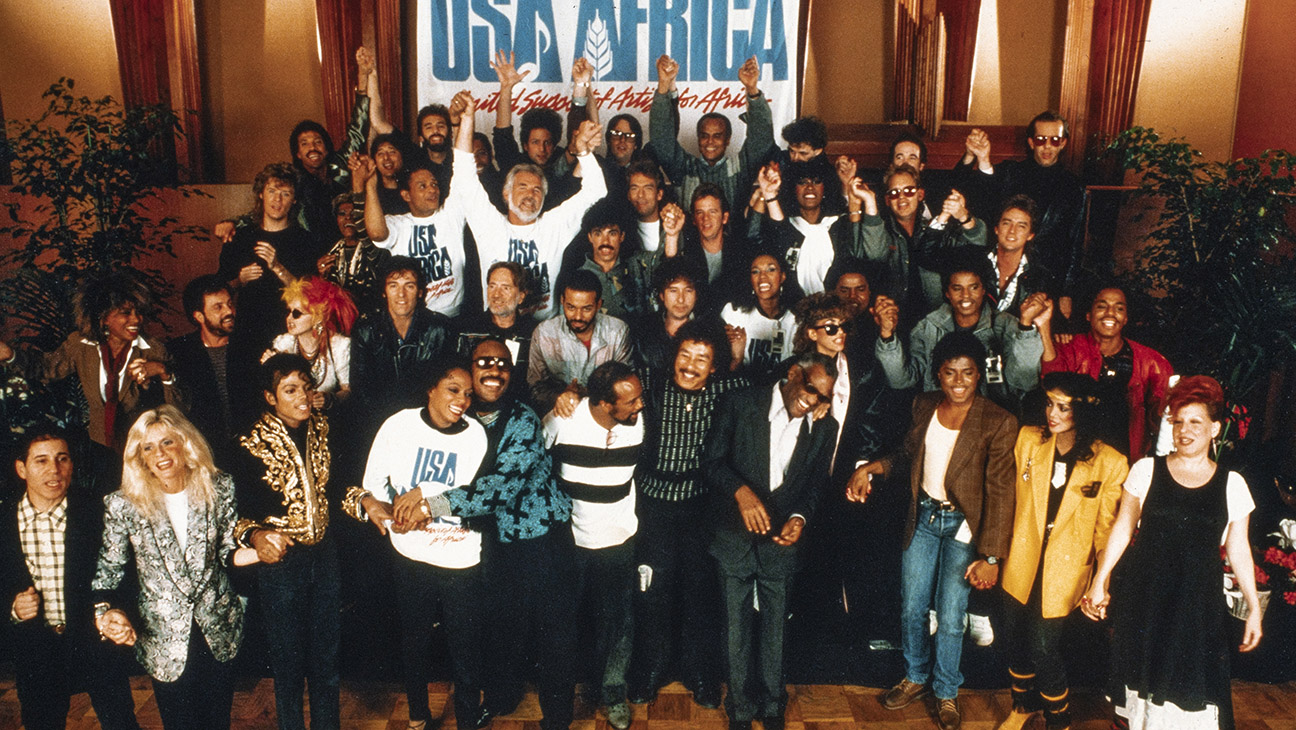

In 1985, some of the era’s most popular musicians — including Michael Jackson, Lionel Ritchie, Stevie Wonder, Cyndi Lauper, and Huey Lewis — gathered in Los Angeles to record “We Are The World,” a charity single for African famine relief. Setting egos aside, they collaborated on a song that would make history. Almost 40 years later, Netflix’s The Greatest Night In Pop looks back on the recording of this now iconic song, exploring what was at stake as the artists raced to put vocals to tape in one night. We spoke with Co-Producers Terry Leonard and Kent Kubena, Post-Production Supervisor Stacy Kessler-Aungst, and Editors Will Znidaric and David Brodie about their experience working on the film and exactly how they got it all done.

Tell us about the genesis of the project. How did the idea come about?

Terry Leonard: When we came on board, the film already had a cut, so our job was to come in and help enhance it. We added to it with new composed music, a new edit, new archival footage, and more to get it to where it is now. Not only that, we shot additional content, including some recreations and interviews with talent.

Kent Kubena: Dorothy Street, the original producers of the project, brought us a really good film and it was our job to make it great. We’re blessed here at MakeMake with some of the most talented storytelling editors in the business who were able to really get under the hood of this treasure trove of footage and pick the best of the best from the material.

Stacy Kessler-Aungst: It was like a relay race — they passed the creative baton to us and we took it and ran with it.

How did you take the story from good to great?

Stacy: One of the biggest questions that came out when we all watched the original cut for the first time was the why of it. Why was this song and this recording so important? What were the stakes? We worked to infuse the fact that they were doing it for hunger and poverty in Ethiopia into the beginning of the film especially, and weaved it throughout. That’s one of the best things that we were able to add.

Kent: Ultimately we also were able to add complexity through establishing the stakes and weaving them throughout the story. There's the stakes of having to get the song recorded and done before sunrise, but there's also the stakes Stacy mentioned, the why of it all. There's a wonderful section in the final cut that talks about the crisis in Africa and how this whole project materialized, which helped illustrate that why. The additional shooting that we were a part of helped enhance the atmosphere of the film as well. We really wanted to give a sense of what it was like in that room for all these icons together.

Terry: We worked very closely with the director, Bao Nguyen, to identify where he still wanted to push it and how we could do so. He really wanted the story to have Oceans 11, bank heist energy, in the sense that the recording of the song happened in one night and it needed to play out in real time for the viewer. We wanted to make sure that the forward momentum to get the viewer into the recording studio was a very powerful, fast, hard push. It was almost like Bao set out to take a normal documentary and flip it upside down, and try to find a different dynamic of how to do it. Will and David were able to weave in what he wanted to do and edit it in a streamlined way.

David Brodie: One of the big things Will and I talked about was the need to make the film accessible to anyone: whether you're 15 or 50, whether you’re the world's biggest Huey Lewis fan or you've never heard of him, you can engage with the film. Finding that balance of explaining who everyone is and why they are important and what their motivations are without slowing the film down was a challenge. We wanted to keep it a narrative and not an exposition, so we spent a lot of brain power on that. Creating a very strong narrative arc for Lionel specifically was important too — we wanted to make sure the viewer sees Lionel's growth throughout the experience.

Tell us more about the editorial process. What was it like to jump in on this project?

Will Znidaric: In our initial approach, [David] Brodie and I started working on different sections of the film so we could get familiar with the style and determine where we felt we could improve things. Bao’s idea of using archival footage not as archival, but as scenes, almost as if this was a scripted film, came out of that process. It wasn't immediately clear from day one, but once we got a handle on it, we were able to find additional archives they hadn't had access to and work those in. They also shot recreations, using the same kind of cameras to keep fidelity to the way the archive looks, and the whole film is a four by three aspect ratio, including the interviews that were shot with 4K. It’s a bold, interesting choice, and it slots you right into the moment in time that this story is taking place.

David: With this approach, every shot had to be very deliberate and it had to tell the audience something. It could never just be a placeholder, it had to tell you something about the era or the location or the characters, and it had to further the story in some way. The finished project is intentional through and through — there isn’t a single wasted shot in the film. Will and I have known each other for a long time, so we were able to trade scenes back and forth and be pretty brutally honest with each other. It was a real gift to have a partner who sees the filmmaking process the same way, so we could do something very quickly at a high level with confidence.

Will: Editing is kind of like an accordion — we push and pull it to find out where the boundary lines are. Some of the stuff we cut initially was just too far out, but we ultimately figured out a way.

What was it like to work with director Bao Nguyen?

David: Bao had a really incredible and specific vision for how the film should look, feel, and move. With his input, we were able to refine his vision and to make the story work within that framework, and ultimately that gave the film a distinct identity and personality that people seem to be responding to.

Will: Bao’s vision of the film following the beats of a heist film created a lot of momentum, interest, and humor. He was very keen on making it as fun and joyful a ride as possible. Though Brodie and I know each other well and had that established trust, Bao didn’t know us like that, plus he was on the other side of the planet. So it was a matter of establishing that trust in the first few weeks, and showing Bao and the team that we've got the same vested interest in creating the best vision of this film that we can. Once Bao came to LA and we all sat in a room together, that's when he really saw that we were all sharing the same vision and we reached a hundred percent trust between us.

Were there any post-production challenges that you faced? And if so, how did you overcome them?

Stacy: The biggest challenge was that there were a lot of people involved that were all very passionate about the project, so we tried to keep everybody feeling enthusiastic and like they're able to contribute creatively, and to make sure that everybody was on the same page. That can be complicated when there are a lot of people involved, but we all worked together beautifully and in the end we succeeded. Just like all the performers, we too had to leave our egos at the door.

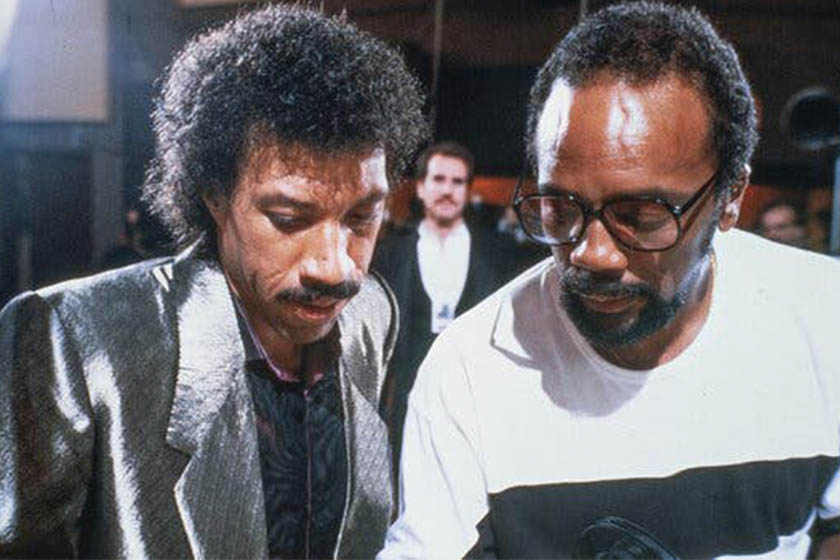

Terry: Between the original production team in England, our team in Los Angeles, Bao in Vietnam, we had to race to get it done in time for Sundance. It truly was a team effort, and everyone was tackling something. We were also lucky that we had Lionel Ritchie working with us — I think because not only was he an ambassador for USA for Africa, but also a producer for the film, he was able to navigate relationships with the other artists' teams in a way that helped us get everything we needed for the project in the timeframe that we had.

Stacy: If you change one frame of archival or add one beat to a song, any changes have to be resubmitted and reapproved by either the artist or whoever owns and licenses that music, or the celebrity or whoever is in charge of the celebrity's estate. You want your editors to have the ability to open things up and make changes, but we know on the production side what that means on the backend — it's a lot of work.

David: Beyond music licensing, you also have to get approval from the estates and the artists. It was part of the process, talking to a licensing team and archival team a couple times a week to analyze what we had in there. Like Terry said, because of the nature of the project and who was involved, there's an inherent goodwill that we were able to use to our advantage. When there were things we couldn’t use, we were able to work around it. Having limitations on the amount of license music we could use forced us to be strategic, and to make sure every scrap of music served a storytelling function, usually introducing character.

Will: The compression of the schedule was definitely a challenge, just how little time we had to do everything. We had to put the pedal to the metal and work together. Certainly one editor alone wouldn't have been able to do it, and even two editors that didn't have that level of trust and admiration for each other couldn't pull it off.

Did you learn any notable pieces of trivia about the artists or the recording process while working on this project?

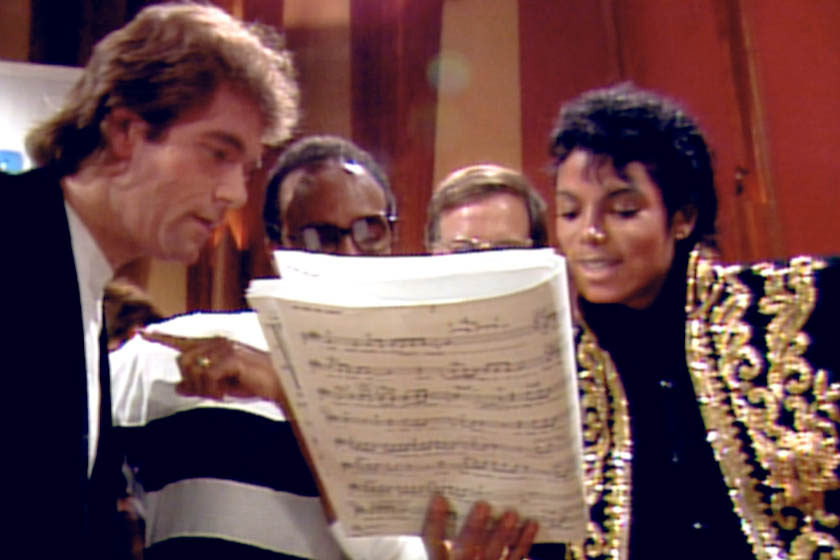

David: I was fascinated by the way Lionel described the writing of “We Are The World” in so much detail, especially when it came to how different approaches to songwriting came together. Since Michael Jackson didn't really play an instrument, he was layering melodies on top of melodies, whereas Lionel writes in a more traditional way, building stuff around chord progressions on the piano. The fact that they worked so well together with differing styles was so cool to me and really shows that you have to stay playful; you can’t let the process become too serious or self-important.

Stacy: For me, it was finding out that Michael Jackson wrote all his songs by humming. Listening to some of the recordings of him doing that blew my mind. I think that’s genius.

Kent: Mine was learning that Huey Lewis’ solo was originally meant to be sung by Prince. It was incredible to be at the film’s premiere with Huey and to be in the room as he watched himself onscreen as a young performer stepping up to the seemingly impossible task of filling in for Prince, and then witnessing the audience giving him absolutely thunderous applause for pulling it off. That was an amazing moment.

Watch the trailer for The Greatest Night In Pop below, and stream it now on Netflix.